The Claremont Review of Books, of which I’m associate editor, has just put out its summer issue. Those of you who found my work through other means may not yet have discovered CRB, so let me take this occasion to say: if you’re at all interested in what I do, you will love this magazine. The honor of working with its erudite contributors and editors is among the highlights of my career to date.

We do four of these issues a year, and I have to say I cherish this one in particular. It’s wide-ranging in subject matter, with penetrating essays on (among other things) T.S. Eliot, affirmative action, James Garfield, and America’s power grid. If, like me, you know nothing about this last topic, you’ll be pleasantly surprised at how engaging it can be.

There’s also an essay by yours truly, on the birth of quantum mechanics and the spiritual revelation that I believe is still underway at the heart of modern physics. This is a subject I’m passionate about, and the essay is sort of a prologue to a new book project I’m working on. I’ve printed an excerpt from it here, and I warmly invite you all to read the whole thing, plus the rest of our issue, at claremontreviewofbooks.com.

A Factory of Idols

To this day, the interpretation of quantum physics is a hotly debated question: what’s at stake is nothing less than the nature of reality and our place in the universe. Those committed to saving a purely mechanical view of nature have come up with various ways to do so under quantum conditions—perhaps, for instance, the multiple possibilities that hover outside our vision are all playing out at once in parallel worlds. But all this must of necessity remain a matter of speculation. If the evidence does not compel, it does at least justify the conclusion that things are simply different when we cannot perceive them. That may be the most profound implication of wave-particle duality. Certainly, it is the one that most severely threatens the premises of the scientific revolution. And those premises are not simply the stock-in-trade of a select professional class. Newtonian mechanics achieved such dazzling success, for so many years, that its picture of the world took on a special authority as the definitive truth about things. “Nature, and Nature’s laws lay hid in night,” wrote the poet Alexander Pope: “God said, Let Newton be! and all was light.” Benighted generations past might have imagined the universe as a disc of earth between two infinite oceans, or a set of interlocking crystal spheres. But now at last the real vision had come into focus, sharp and clear as a mathematical equation: reality was a great infinity of space, occupied by bodies in motion. It is not too much to say that classical physics attained an almost scriptural authority over what could be considered absolutely real, as the Church in Galileo’s day feared it would.

Every kind of physics begins by asking us to picture the world a certain way. “Imagine everything riding on the back of a turtle.” “Picture a grid extended infinitely in all directions.” “Think of Venus fixed within a hollow orb.” The test of the picture is how exactly it predicts the future: we cannot see the turtle, or the grid, or the orb. But if they were there, what would happen to the things we can see? The hope and the promise of classical physics was to settle on a final picture once and for all, not simply as a convenient working model but as an absolute truth. That was the point of “primary qualities”: certain aspects of the world might be figments of human experience, but others would stand fixed for all time in the absolute certainty of mathematics. “Philosophy is written in this grand book, the universe,” declared Galileo in The Assayer (1623). “It is written in the language of mathematics, and its characters are triangles, circles, and other geometric figures.” If it could be quantified, it could be counted on: the raw truth of things was bodies moving through space. We might bear witness to them, but we had no part in their creation.

This in itself was a revolution. An older approach was to use mathematics only for the sake of “saving the appearances.” This meant finding pictures and models that would account for how things appear to us, without asking what is “behind” the appearances. However closely we peer at things, however carefully we parse our sensations, we will only ever by definition be experiencing a set of human perceptions. The numerical abstractions we use to predict and describe these experiences are not some “deeper” reality “beneath” our perceptions: our mathematical models really are models. However sophisticated they may be, they are not the bedrock of existence. “A map is not the territory it represents,” wrote the scientist Alfred Korzybski in 1933 (Science and Sanity). All models are wrong, but some are useful: thoughts never occur without images, as Aristotle understood (De Anima 431a). But the image is not the thought.

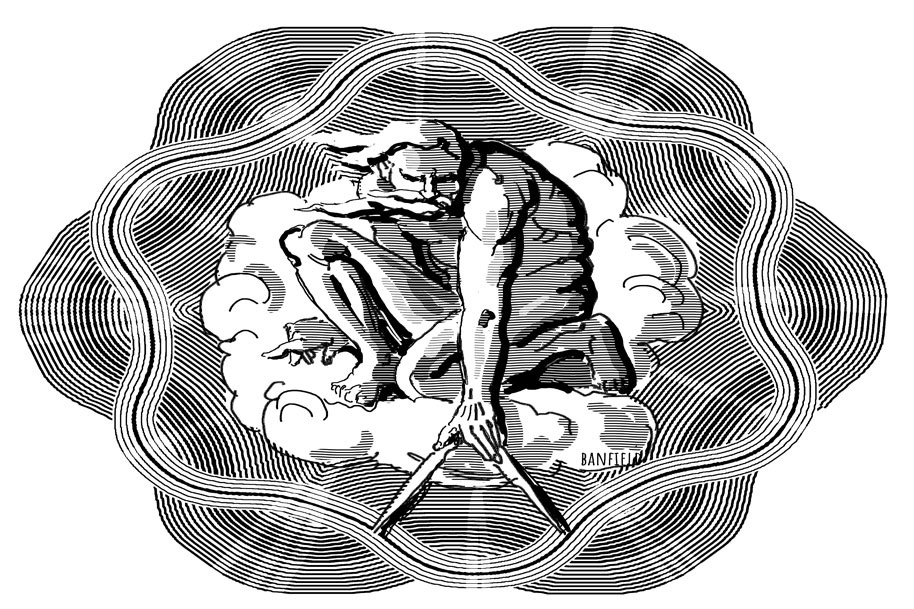

We know this. But it is easy to forget. What we long to do is reach beyond the veil of our humanity, to touch and see the world behind the screen of our perceptions. What we do instead is take our pictures for reality, confusing our physical models for the immaterial things they represent. In the Christian tradition this is called “idolatry,” a confusion between an eidōlon—i.e., an image—and the thing it depicts. A statue of a god becomes a god. The power of a human king replaces the divine power that it stands in for. Matter replaces spirit. Pictures replace the truth.

The picture of things that emerged from the scientific revolution—a world stripped naked of human feeling, its contents churning through space like parts in a machine—came to stand for generations as the absolute truth, the reality behind which there is nothing else. At the bottom of existence there are “quantities of matter”: that is still the world picture taken for granted in our pop metaphysics. “We’re all just made of molecules and we’re hurtling through space right now,” cheered comedienne Sarah Silverman as she accepted an Emmy award in 2014. “Atoms in our bodies trace to the remnants of exploded stars,” mused the celebrity physicist Neil deGrasse Tyson in a viral tweet. “All things are made of atoms—little particles that move around in perpetual motion,” asserted Richard Feynman, one of the greatest physicists of the last century, in his undergraduate lectures at Caltech. The picture of matter in motion has stuck in the popular imagination as the final truth of all things.

For a century and more, this picture of the world has been dissolving. It was only ever a model—another image of the world beyond our sight, useful but ultimately false. But like the priests of some old stone god, the most enthusiastic acolytes of classical physics took its imagery for literal reality. Even as that imagery has frayed around the edges, its popular appeal has not waned. As a result we have been living—we are still living—on the painted stage of a pagan universe, imagining that our pictures spring to life when we’re not looking.