The days are getting darker; soon the world will be reborn. Gliding smoothly under our secular calendar, which restarts with a juddering gear-shift in January, the signs and markers of the heavens trace a pattern of things unseen.

Christians begin their cosmic year in late November or early December, with Advent’s stately descent into winter. There, in the deepest cavern of the dark when the day fades to a cold slip of light, Christ is born.

Unlike Easter, Christmas celebrates an event whose place in the historical calendar—the calendar of things seen—is difficult to pin down. But In his sermons on the day, St. Augustine returned again and again to the rightness of December 25 as a symbol of God’s entry point into our valley of death.

“He, therefore, who bent low and lifted us up chose the shortest day, yet the one whence light begins to increase.” The light that slips in under cover of dark, and begins to grow: that’s the new creation.

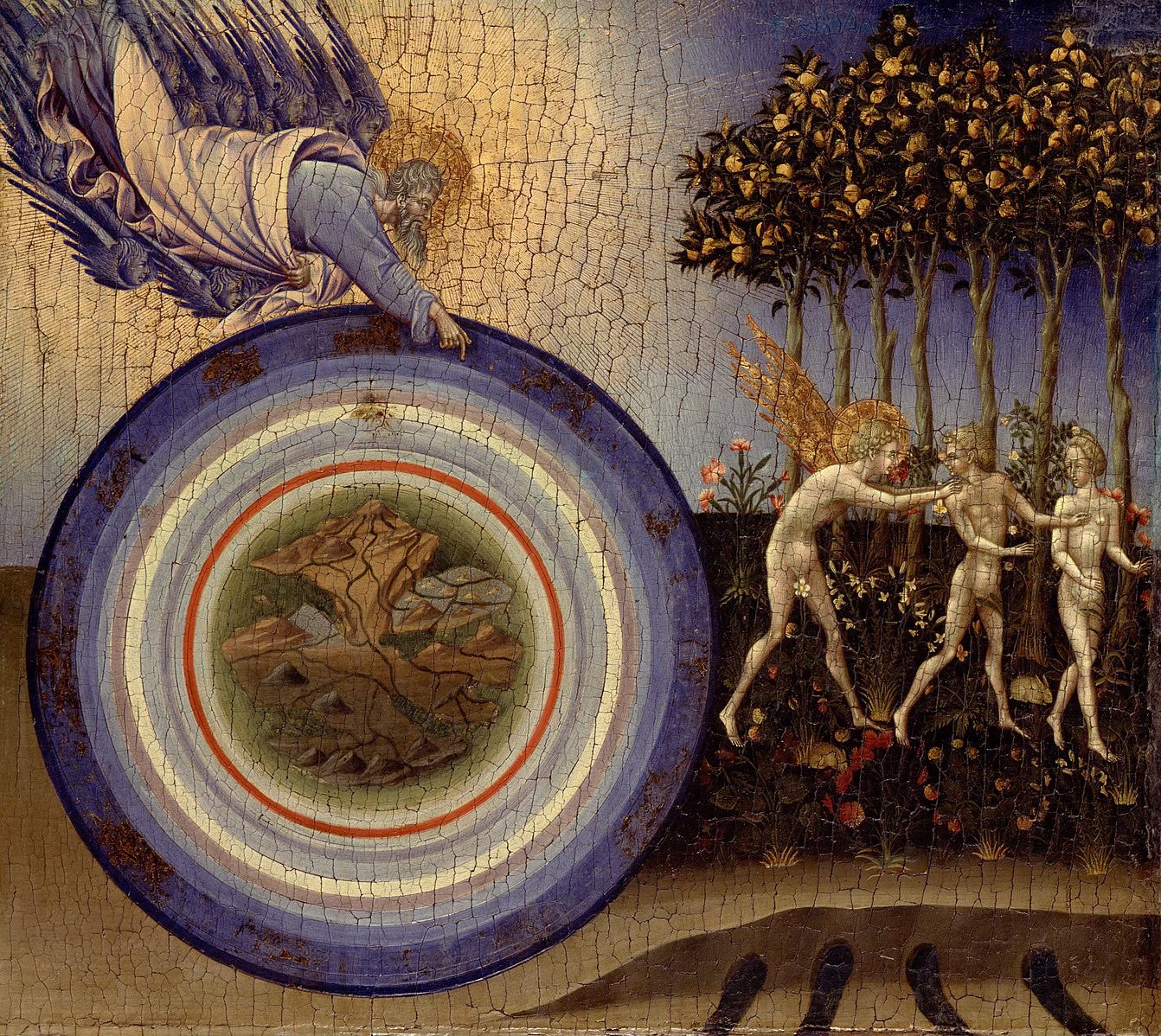

This week, though, the Jewish calendar marks the first creation, the making of the world before corruption warped it. A little like us, the ancient Jews celebrated new beginnings at a number of points on the calendar, making for four new years in total.

One is the political and ecclesiastical new year, the beginning of the festivals with Passover and the ascent of kings to the throne. But until this evening Jews around the world will be observing Rosh Hashanah, the “head of the year” and the capstone day of Genesis. It is the start of all things.

Just before the holiday began I recorded a podcast (to come out in a couple weeks) with consummate mensch Brian Keating. Brian’s a world-class cosmologist—which is to say that Rosh Hashanah is kind of his bread and butter. But he pointed out to me that technically, according to Rabbinic tradition, the festival commemorates not the first moment of creation, but the creation of man—the moment Adam and Eve woke from sleep.

In the Bible, the festival is called not Rosh Hashanah but Yom T’ruah, the day for shouting and blasting the trumpet. Rebbe Nathan Sternhartz’s Likutei Halakhot, a sprawling 19th-century commentary, interprets this hullabaloo as signifying “the arousal from sleep” when mankind’s eyes first opened.

But it’s interesting (I am trying to constrain myself from saying, it’s freaking metal as heck) that this moment is tied so closely in the texts to the creation of the universe itself. Citing the ancient Babylonian Talmud where the scaffolding of the calendar is laid down, Sternhartz goes on: “the shofar [trumpet] represents arousal from sleep, since ‘the whole world was created in Tishri’ [the month we’re in now].”

It’s almost enough to make you think that when man’s eyes open, that is the ultimate creation of the world, or at least its consummation. As far as Jesus was concerned, “the sabbath was made for man, not man for the sabbath”—suggesting, at least to me, that man isn’t dropped into the seven-day structure of Genesis as an afterthought. He’s placed there as a keystone, the final piece that holds everything together.

This is, not coincidentally, what my new book is about. Light of the Mind, Light of the World is a new history of science in which I argue that physics is starting to describe a world that looks a lot like the one in Genesis, where the meeting between human consciousness and material creation gives the world its final form. Here’s how I describe it in the book:

At some moment a creature was born who experienced not merely a succession of unconnected sights and sounds but an interconnected web of forms and species, a world of things living and dead connected through time. In that moment the sun rose as never before on an earth that could be understood by someone within it; the days and nights took on a rhythm that could be felt, and one by one the animals received their names. It is not too much to say that even past, present, and future took on a new shape, and only then was the work of creation complete.

It’s been proposed that the Imago Dei, the insight that man was made in God’s image, is the Jewish people’s single greatest gift to the world. Rabbi Jonathan Sacks called it “perhaps the most transformative [idea] in the entire history of moral and political thought.” If human consciousness really is a formative component of the universe, necessary to complete even material reality as we know it, then the gift of God’s image in us reaches deeper into the bones of things than we have even yet imagined. We will never exhaust it.

And this year, when the nations rage so viciously at that image, when armies rise up to snuff it out and technologists promise to surpass it, when the people who handed down that gift for centuries are threatened daily with annihilation—this year of all years, see how good and how pleasant it is to wake in defiance from sleep and remember who made the world, and who made us. Shana Tova.

Rejoice evermore,

Spencer

Listen to the latest from Young Heretics:

The past few weeks I’ve been sleuthing through the satanic Hollywood/elite drama, and it had me feeling downright paranoid.

And then I went to Rosh Hashanah services and read from the Machzor, the prayers by which we admit our humility before God and his design, and I felt like everything was ok.

Beautifully stated Spencer!