Poor Unfortunate Orcs

I'm calling for a complete and total shutdown on misunderstood villains.

Children are innocent and love justice; while most of us are wicked and naturally prefer mercy.

—G.K. Chesterton, “On Household Gods and Goblins”

It gives me no pleasure to say this, but Wicked and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race. I’m afraid we have to talk about it, because there are Orc Babies now in Rings of Power and it’s Gregory Maguire’s fault. Things are clearly getting out of hand.

Back in 2003 the musical, based on Maguire’s 1995 novel, delighted teenage theater kids like me. Composer Stephen Schwartz is no Cole Porter, but his lyrics had enough quirk and self-awareness to elevate them just slightly above the level of twaddle.

But the explosive success of Wicked inspired a mania for what you might call the “Misunderstood Villain” trope, which was Maguire’s most dubious conceit and unfortunately also his central idea. If you want to know “why is Frozen?” look no further (and I’m sorry, but “no right no wrong, no rules for me” is the anthem of a sociopath).

Important disclaimer: we are not concerned with misunderstood or redeemed people, of whom there are many in both real life in art. I have no beef here with Beauty and the Beast or Crime and Punishment or even the Star Wars prequels—with origin stories or anything else about flawed characters secretly being, once having been, having the potential for, or becoming, good.

My problem is specifically with the sadistic form of canon violence that occurs when a spinoff or sequel takes someone whose evil was the point of his role in the original story to begin with, and enlightens us about his difficult childhood/sympathetic motives/secret virtues/fondness for dogs.

Evil stepmothers and wicked queens are odds-on favorites for this treatment because of the implication that the world just couldn’t handle a powerful woman who dared to skin puppies for coats (SLAY, kween). But there are other versions too. Entries in this genre include Cruella, Maleficent, probably the new movie with Dave Bautista as the monster from Beowulf, and absolutely anything in which Satan was just trying to help (e.g. Hazbeen Hotel).

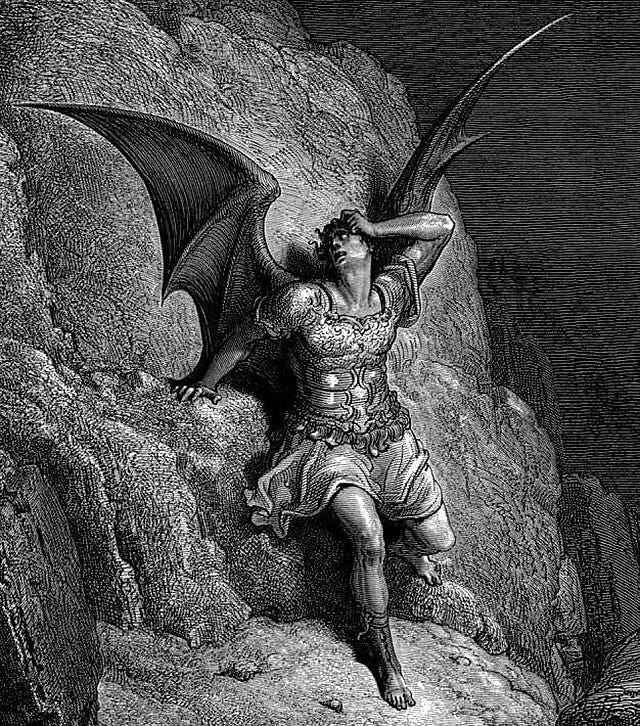

Gregory Maguire didn’t invent this particular narrative device. William Blake might have, when he pioneered the (kind of silly) idea that Milton inadvertently portrayed the devil as a tragic hero in Paradise Lost. Or else we can blame Gnosticism, an ancient form of retconning that casts the God of the Bible as a deceitful scoundrel (the modern reboot of which is to be found in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy).

Some versions of “Misunderstood Villian” are moderately entertaining, but all of them are by nature derivative and ultimately, if you think about them for a second, incredibly dumb. Stories are about people making choices (see Aristotle, Poetics II.1448a). Choices can be morally right, wrong, neutral, or #complicated; it’s up to the author to present those choices and the people making them in a way that’s plausible, interesting, and revealing.

And in some cases—especially myths and legends—it’s important that there are characters who choose evil. Sometimes there’s a reason why: “since I cannot prove a lover…I am determined to prove a villain” (Richard III I.1.28-30). Sometimes the villainy is just one of the given data points of the fictional world, like the existence of invisibility cloaks and flying brooms.

But either way the plot depends for its logic on the stipulation of a person who has chosen evil and therefore is evil. Whether it’s explained later or not, whether the evildoer faces repentance or justice or death or whatever, the author has invited you to play a game where you imagine that once a sinister wizard locked a beautiful maiden in a tower and the brave prince had to come save her.

You can of course refuse to play along—you can insist that the tower was actually a garden shed and the wizard was actually a sweet old man—but then you’ve ended the game and invented a new one. Made-up people, the way they are, and the things they do, are everything there is to a story; they are all the author and his readers have.

Grendel isn’t a monster because the creator of Beowulf was a spiteful little nudnik; Grendel is a monster because the creator of Beowulf wanted to portray the existence of a certain kind of spiritual ugliness. To make him even a touch less grotesque isn’t to flesh out the narrative but to rewrite it.

The irony with the peace-loving Orcs in Rings of Power is that all evil in Tolkien already has an explicitly defined and morally sophisticated explanation. In a letter to his prospective publisher, describing what he called the Machine or bad magic, Tolkien wrote, “this frightful evil can and does arise from an apparently good root, the desire to benefit the world and others.”

In the LoTR mythology, supreme demons like Sauron and Melkor/Morgoth initially aspire, like the Elves, to superintend the lower-order creation and heal its defects. To do so in an organic way that leaves lesser beings free is a form of what’s called “sub-creation”; to do so through artificial or forceful interventions “for their own good” is a form of perversion that naturally degrades over time into the sheer will to power.

Since people who try to abolish death mechanically do in fact end up forcing their fellow beings into hideously unnatural subjection and consigning them to a constricted shadow-life (see, for example, the COVID regime), Tolkien’s theory of the case is a profound one. And though Tolkien believed this descent into evil could be traced and understood, a central point of his philosophy was that it really was evil, deserving of blame and opposition—not misperceived virtue or one among a number of valid points of view.

The problem in the streaming version isn’t that the orcs reproduce, which Tolkien indicated was possible. It’s that they seem to just want peace, which would make them…not orcs. “We will never truly be safe until we’ve made certain Sauron is no more,” their leader says. But safety is by definition not what the orcs want. They want power.

To be Lord of the Rings, the story has to include the existence of characters who have fallen into a recognizable but nonetheless avoidable error, with catastrophic results. Stories that portray such errors, and people making them, aren’t small-minded or hard-hearted: they’re honest. The “Misunderstood Villain” trope is ostensibly just about showing that one character isn’t as evil as we thought. But the implication is that no one is evil, not really. And much as I wish it were so, it just ain’t.

Rejoice evermore,

Spencer

Listen to the latest from Young Heretics:

Snow Queen color image: Elena Ringo http://www.elena-ringo.com, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

This trope isn't just bad for retcon reasons. It deflates the dramatic tension of the story. Shylock is a sympathetic and complex antagonist, but his antagonism is brutal and intransigent. Any attempt to nerf that evil is going to rob us of the pucker-inducing tension culminating in that magnificent courtroom scene.

That's "why is frozen."

I think the instinct to de-villify villains comes from the spasming consciences of increasingly degenerate writers. This was certainly the case with William Blake (although he managed to do it without becoming a lousy writer, somehow). I think modern writers experience inner shame because they often live shameful lifestyles, and seek to soothe their consciences by rationalizing away society's moral instincts.

Like the fat positivity movement fighting fat-shaming, this is the evil positivity movement fighting evil-shaming.

Rather than turning to Christ in repentance, asking their evil to be swallowed up in His atonement, they deny sin altogether, and so imagine they need to repentance.

Totally agree. Another example of this phenomenon: Rebecca's Tale by Sally Beauman, a revisionist version of one of the most popular novels of all time, Daphne du Maurier's Rebecca. One of the ways our previously-Christian culture has become ensnared is through the manipulation of empathy: If we just understood and felt the feelings of deviants and other insistent sinners, we would not condemn them but see them as victims and feel sympathy for them. Foreseen in various places in the book of Deuteronomy, where God's people are told to "show no pity" on the idolators who were delivered into their hands because they would ensnare their hearts. And ensnare they did.