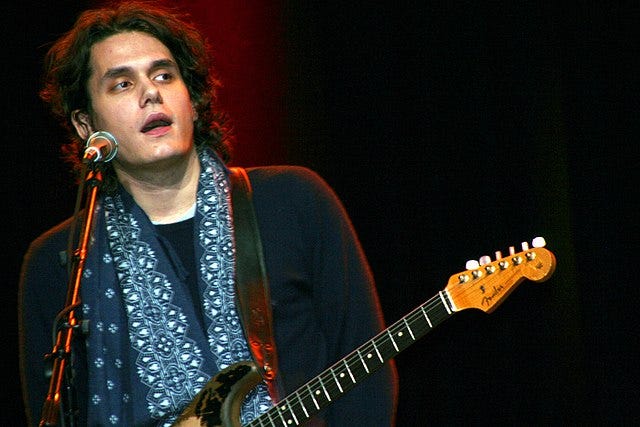

I was 10 when John Mayer’s Room for Squares came out in 2001. For me, the album carries that year along with it through time. Whenever it comes on, it comes trailing the smell of the Pacific and the curl of sunlit California mist. My coolest friend, who wielded his own guitar with an effortless assurance that only Mayer himself could surpass, had downloaded the whole thing on Limewire. The man’s voice sounded like barbecue smoke and his riffs felt like wanting to grow up. It was our drug of choice.

It also made me uneasy. The album’s debut single, “No Such Thing,” was about shrugging off the pretensions of social expectation and running free through the halls of your old high school, screaming at the top of your lungs: “I just found out there’s no such thing as the real world / Just a lie you got to rise above.” Adults might tell you how your life should go, but what did they know? The future was what you could make of it.

Catnip for fifth graders—except I wanted to believe in the real world! Its neatly determined metrics and outcomes were working out just fine for me. I had sweated hard over the grades I was already stacking up like chips in a casino, and it was important for me to believe that the house did not play dirty. Honor and spoils should accrue to the most deserving—of this, even at 10, I felt deeply certain.

So as much as I loved John, I would never let his siren call seduce me away from the hero’s journey that lay ahead: AP classes, then the Ivy Leagues, then surely fame and fortune. It was all very well to cast knowing aspersions on the real world if you were a rock star and you could afford a little Bohemian nonchalance. But I had a job to do.

Those closest to me will surely agree that my ego and ambition remain just as comically outsized as they were when I was a pre-teen. But something strange has happened in the years since Room for Squares came out. It feels more true to me now, not less, since I grew up. What once felt like the posturing of a garden-variety hipster now feels like a prescient description of the decades ahead. At some point, it started to seem like there was no such thing as the real world.

I don’t think it’s just that my particular life has taken more than one unexpected swerve. I talk to college kids now and I’m struck by how totally uninspired they seem by the prospect of a well-paying, stable, 9-5 job in their chosen field. And what’s funny is these aren’t the delinquents or the artists: these are the highly driven kids, the ones on the grind. They’d happily welcome some conventional wisdom, if any were forthcoming. It’s just that none of our conventions seem all that wise to them.

Instead, what lights them up is the idea of crafting a job for themselves out of nothing; watching videos on YouTube until they know how to build what they want to build; emailing their favorite online entrepreneur and taking on an apprenticeship that didn’t exist until they asked for it. The most successful people now are definitively not the ones who hit the milestones that their parents can recognize. They’re the ones who see the shape of an entirely new landscape, and who don’t ask permission before staking out some real estate for themselves.

The image that has loomed over this week is Donald Trump’s mugshot, posted dramatically on Twitter/X, in which he stares defiantly out at Georgia law enforcement and at us. My readers will know what side of this dispute I am on: for all my criticisms of Trump since 2020, I think the indictments against him amount to shameful and dangerous acts of political persecution. But the interesting thing is that even if you disagree with me entirely about this, you will still think that the whole saga represents a collapse of national stability—just on the other side of the equation. Whether you lay the blame on Trump or on his opponents or somewhere in between, we are in dramatically new territory. I don’t think we are going to turn back around.

In times of stability, cultural iconoclasm is mostly exclusive to rock stars and poets. But when practically every body of authority is hemorrhaging public trust, the iconoclasm of the beatnik becomes the winning strategy of the most productive citizens among us. Increasingly I feel as if there’s a future layered secretly under the official picture of the present that our institutions still draw, a new world emerging like a palimpsest under the fading outlines of the old.

This is a tectonic shift too laborious and far-reaching for us to see it clearly while we’re in it. I even wonder sometimes whether we don’t stand poised to resurrect the Middle Ages, in the same way that the architects of Renaissance resurrected the classical world. Something forgotten is being recovered in a new form—the tradition of the guild and the cottage industry, young men and women discouraged by the corruption of their leaders forming homesteads anew in the idiom of the digital age.

For what it’s worth, here is my prediction. The optimism of the American century, the easy assumptions of modern materialism, even the proud confidence of the Enlightenment: all this is passing away. An age of mysticism and high drama will replace it, better in some ways and worse in others than the one we grew up in. The change will probably not come without still more upheaval and turmoil. But for all the ruin and collapse that seems ongoing, it’s not just downfall that we’re facing. It’s the birth of something new, too. And it may be that, as my boy John Mayer said, “something’s better on the other side.”

Rejoice evermore,

Spencer