Let’s check in on how the horrors beyond our comprehension are incubating. Indulge me in a pop quiz: is this a real woman or an AI fake?

(No cheating. Scroll down for the answer.)

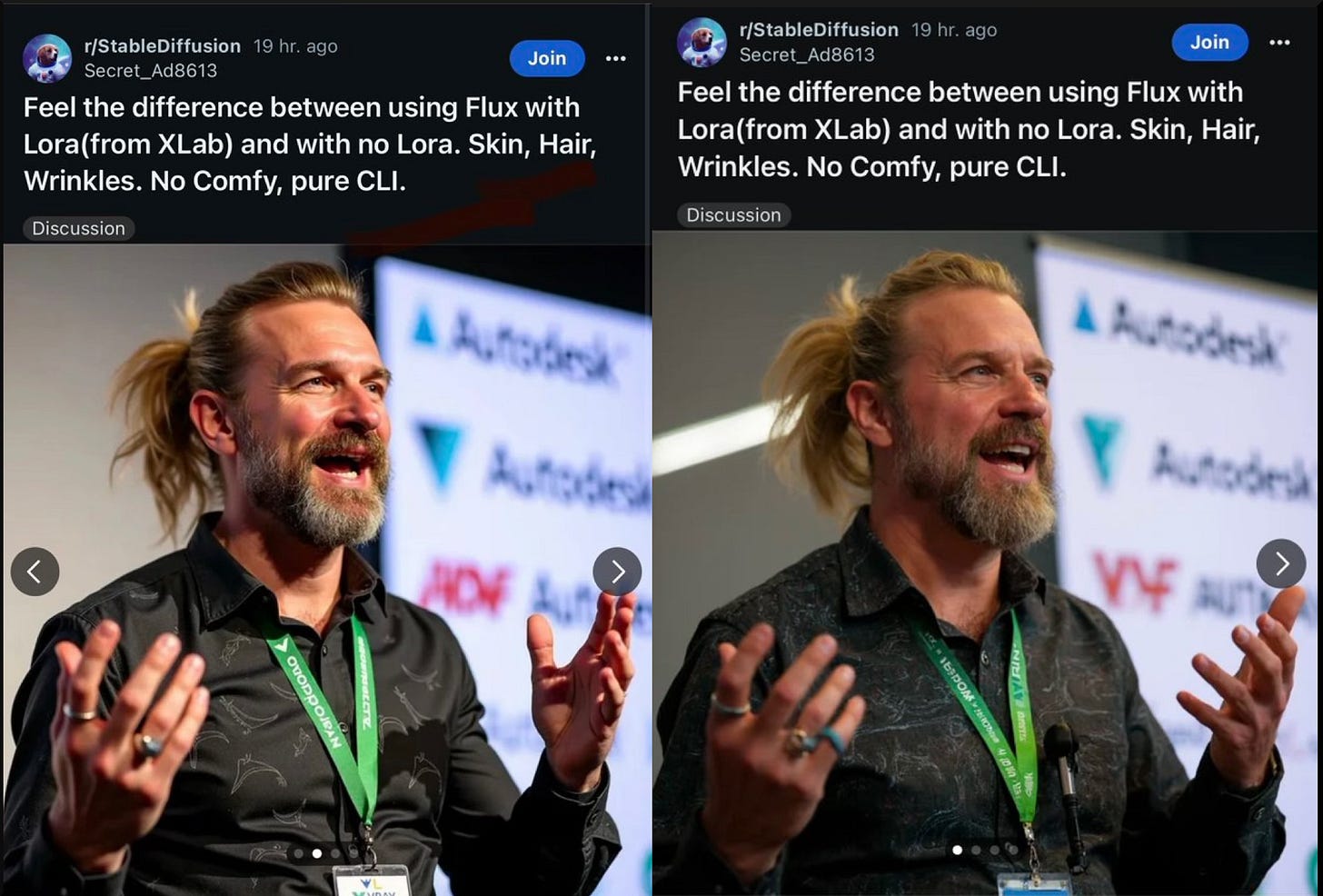

Answer: ceci n’est pas une femme. Whatever a woman is, it ain’t this, which is the product of the image generator Flux plus a LoRA—basically an add-on that fine-tunes a generator without overhauling its whole system. In this case, it counteracts the unnatural smoothing that happens when AI programs sift through jumbles of pixels to shape an image. It gives you creases and textures to chip away at that CGI look. Here’s the difference it makes:

User @kyrannio, who introduced the image of the woman to Twitter, admitted that it pulled her up short. It did me too. Then I started scrolling through the little details people had caught: her lanyard is warped at the clip; the writing on her microphone is garbled; the patterning on her dress is glitchy at the waist.

What stood out to me was something of a slightly different nature, less dispositive but perhaps more telling: she’s wearing what’s clearly supposed to be a wedding ring, but it’s on her right hand. I find AI eeriest when it’s like this, on the razor’s edge of meaning. Nonsense can be unsettling, but nothing quite gives me the creeps like something that almost makes sense, yet doesn’t quite.

It’s the cold chill of The Objective Room, the satanic training ground where the hapless Mark Studdock finds himself near the end of C.S. Lewis’s That Hideous Strength. Every feature of it is designed to thwart and subvert the natural human instinct to discern ordered forms. This includes the paintings on the wall, each of which is just slightly off:

The apparent ordinariness of the pictures became their supreme menace—like the ominous surface innocence at the beginning of certain dreams. Every fold of drapery, every piece of architecture, had a meaning one could not grasp but which withered the mind.

In the real world, every picture is two things at once: a wall and a window. Walk into an art gallery and you know you’re looking at daubs of paint on rectangles of flat canvas. That’s the wall. But with good paintings you have to work to see things that way. It’s more natural to fall through the window and see the thing the painting represents: a storm at sea, a woman’s face. A pipe.

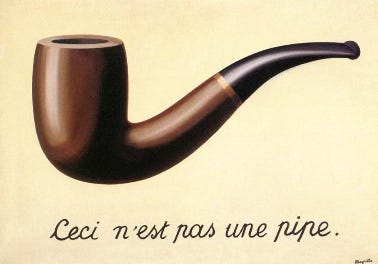

This is why there’s something diabolical about that painting by René Magritte, The Treachery of Images (1928-9):

“This is not a pipe.” It’s about how images can betray you into thinking they are what they depict. But it’s also itself an act of treachery against all images and the magic act that makes them work. The mind rushes to fly through the window into the world of the painting, but finds it slammed shut.

Thomas Aquinas, citing Aristotle, writes that in the presence of an image “there is a twofold motion of the mind.” One is toward the thing as an object like any other, a sheet of wood or a hunk of marble. The other is through the object toward the form of the thing, translating raw matter into shapes and spirits.

On the far side of the window waits another human soul, lifting a corner of its veil to offer facts or visions from its private treasury. What Magritte called deception is really translation, encoding pure thought and feeling into the stone and slime of mere things.

We have to believe translation like this works, or else not just art but language and even physical perception are empty illusion, a scudding foam of deceit on the churning sea of atoms in motion. An image is defined not just by what it looks like but by where it claims to come from, the reality at its source.

Sometimes, as in a portrait or a newspaper photograph, that reality is supposed to be the material world. Sometimes it’s supposed to be the world of the artist’s inner life. In both cases the viewer slips over a threshold into the depicted life beyond.

What spooks us about AI is what’s unnerving about Magritte’s pipe: it makes us stumble at the threshold. With media we’re used to, the mind strides confidently from the surface of the symbol to its heart. But image generators leave us wobbling like young deer.

I can imagine we might learn to walk on this new ground—to use these programs and interpret their products accurately. Generations after us might become fluent enough to translate naturally from AI-simulated dreamscapes to what their developer intended to express by them. We learned how to do that tolerably well with video games and CGI.

But whatever language can be used to speak truly can also be used to lie. I don’t know which will outstrip the other: our capacity for deceit or our faculties of discernment. But that’s the race, and I’m not giving it up for lost yet. The soul is a powerful translator—the best one yet designed. The model that was installed into humanity, at the foundation of the world, remains the latest and greatest on Earth.

Rejoice evermore,

Spencer

Listen to the latest from Young Heretics:

It's creepy how far technology has progressed. And it's also a bit creepy how prophetic Lewis appears to be - especially in That Hideous Strength.

As for the wedding band: is AI anti-American, or at least globalist? In many cultures across the world--save the US and our neighbors to the north--wedding bands are worn on the right hand.