It was a perfectly gripping thriller—too bad about all the God stuff. This was the considered opinion of Eric Arthur Blair, better known to the world as George Orwell, upon reading the greatest novel of Mr. C.S. Lewis.

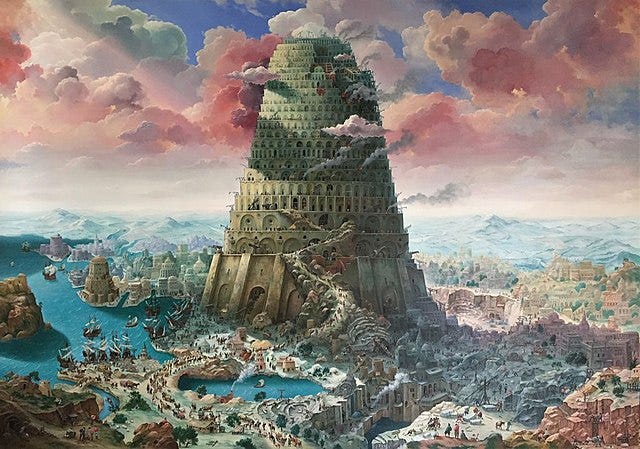

That Hideous Strength is the conclusion of Lewis’s Space Trilogy; it can be read independently of the first two books, because its central drama takes place not in the heavens but on earth. Furtively but resolutely, in a secluded manor house, an elite corps of theorists and technicians are conspiring to become masters of the universe.

They flatter themselves to have risen above the petty delusions of the common man, their minds wiped clean of spiritual confusion, their steely gazes fixed with lordly resolve on the domination of time and space. Under the credulous dispensation of various government dupes, they have organized themselves into the National Institute for Co-ordinated Experiments: the N.I.C.E.

All this is very plausibly imagined, wrote Orwell in the Manchester Evening News, except that the author insists on ornamenting his plot with a confused menagerie of sprites and demons. As a political satire the novel succeeds almost beyond qualification. But “Unfortunately, the supernatural keeps breaking in.”

Except that was the whole point. Lewis was not the only person to watch with horror as a new class of technocrats arose, terrifying in their self-assurance and insatiable in their limitless hunger for power. Orwell himself had seen that far in his own non-fiction; in 1984 he would go on to write one of the definitive cautionary tales about exactly this sort of megalomania.

But Lewis went further. Precisely his reason for writing That Hideous Strength was to peel back the thin skin of the merely material world and reveal the cosmic forces locked in battle underneath. The angels and demons are not extraneous intrusions from a world “outside” or “beyond” the main political narrative: they are the exact same political narrative, seen from another angle.

Orwell was among the the most keen-eyed observers of his generation. That he could be blind to the spiritual dimension of things, or at least not see what Lewis was trying to say about it, shows how thick a fog of secularism hung and still hangs around the most educated men.

Which, of course, is exactly why the schemers of the N.I.C.E. don't fully realize the nature of the demons they’re collaborating with until it’s too late. The whole genius of the novel is to show that what looks from one side like a purely human affair is always, seen from the other side, a cataclysmic struggle among the dominions of heaven and hell.

This struggle, though usually among the “things invisible” to our physical senses, is not going on in some alternate and distant plane. It is surging and throbbing in the movements of this earthly realm, pulsing beneath the physical world like golden light behind a dark scrim.

Monsters and archangels don’t have to be “brought into” human literature from some foreign land. They have to be made visible by poets who can translate the spiritual drama into the language of flesh and blood. Lewis, who knew this, was a greater realist even than Orwell, who did not. It all depended on understanding what is real.

Rejoice evermore,

Spencer