The only time I have ever fallen asleep at my desk was the summer I worked for Yale’s college admissions office. I was a student interviewer, meaning I sat for half an hour with kids not much younger than myself and tried to coax out of them some indefinable glimmer of personality that would distinguish them from their many, many peers.

It wasn’t a boring job by any means, but it was a repetitive and exhausting one. The vast majority of applicants were gentle, earnest, hard-working souls. All the same, not even a breathless idealist like me could deny that after about a week they all started to look and sound the same. Which is why my boss walked in on me taking an unintended power-nap—not, mercifully, during an actual interview but just before conducting my sixth of the day. It was to be much like my fifth.

It would be cruel and insane to expect more differentiation among these kids, especially after shunting them through a manic seventeen-year circuit workout of ever-accumulating APs and extracurricular commitments. As Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry pointed out recently, you just don’t have much that’s original to say about yourself at that age. Ironically the most authentic thing you can do is to realize this and submit to rigorous training in various useful disciplines.

At the same time, the pit crew of tutors, advisors, parents, and teachers who coach the really driven types are always telling them (correctly) that one of the first major turning points of their career will hinge on whether they can communicate some intangible set of character traits that marks them out as individuals. The point of the interview, like that of the notorious personal essay, is to elicit signs of the ineffable qualities that otherwise can’t be conveyed through test scores.

What are those qualities? The question came up yet again this week when a young man posted his solid GPA, a series of rejections from high-profile schools, and an essay in which he humble-bragged his way to the realization that building calorie-tracker apps isn’t all there is to life. Discourse ensued.

Not that it matters much, but if I had been coaching him I would have said that his problem wasn’t so much parading his net worth around as failing to show any awareness—besides a sort of muddled passage where he gazes vaguely at rocks in a zen garden—of what higher education could add to his life besides more of the money he was already earning.

But then, that’s exactly the problem. No one can really say at this point what college does besides make you more marketable, and it doesn’t really do that very well anymore either. The app guy (his name is Zach Yadegari) began by pointing out quite rightly in his essay that you can get seriously lucrative skills on YouTube.

It would be nice to say that immersion in the liberal arts would take those skills of Zach’s and orient them toward the good, the true, and the beautiful. It’s still just possible that it might, if he got lucky and smart in his choice of instructors. But more likely, four years at Harvard would only train him to position himself in an ideologically war-torn landscape amid Hamas enthusiasts, intellectual snake oil salesmen, and HR functionaries.

In other words it’s hard to see what the value-add of an elite degree course is for Zach, besides that it would train him in exactly the sort of social signaling that he failed to perform quite deftly enough in his essay—the art of cloaking his actual competencies in the courtly language of the social aristocracy.

To some extent, American colleges have always been in the business of filtering for that aristocracy. “In the absence of a system of hereditary ranks and titles,” wrote Paul Fussell in Class, “Americans have had to depend for their mechanism of snobbery far more than other peoples on their college and university hierarchy. I like to think it’s a bit more complicated than that, but not much.

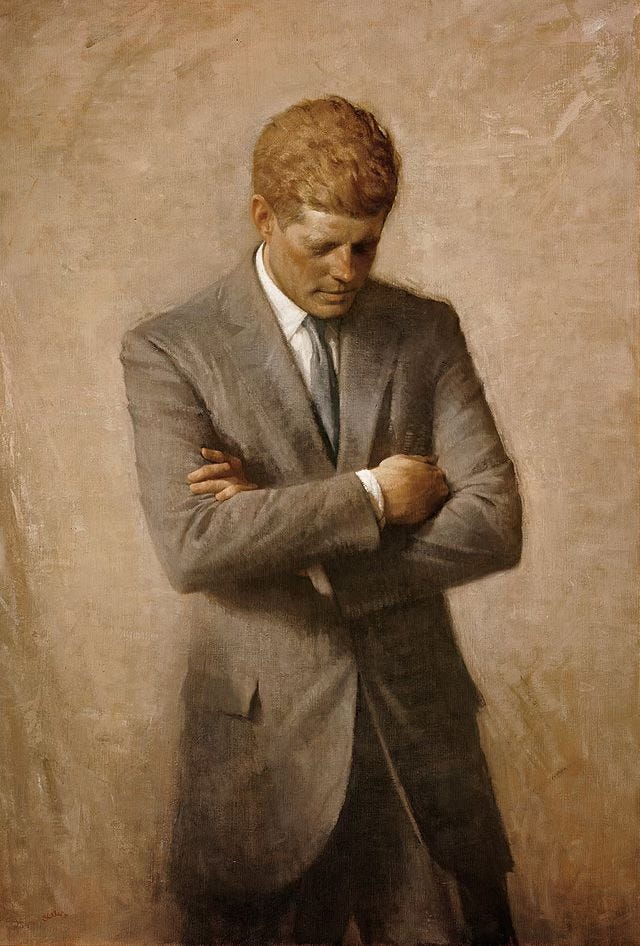

“I would like to go to the same college as my father,” wrote JFK at the end of a 91-word Harvard essay in 1935. “To be a ‘Harvard man’ is an enviable distinction, and one that I sincerely hope I shall attain.” When democratizing forces and market pressures made it harder and harder to be explicit about the social dimensions of what it meant to be a “Harvard man,” schools had to come up with clever ways of masking what they were looking for. Hence the delicate performance art of the modern college essay.

I suspect a lot of “wokeness” in schools is actually downstream from these imperatives. Harvard has been at the center of two national scandals this decade: one in which its president turned out to have plagiarized major portions of her academic work, and another in which the Supreme Court found that its admissions practices discriminated against Asians and whites, in part by docking them points on precisely those murky “personality” scores that are meant to counterbalance their obvious superiority in quantifiable academic achievement.

Both of these disgraces involved using made-up forms of spuriously measurable excellence as workarounds for passing off social engineering as meritocracy. If you want to screen out undesirables while also feigning openness to all, you have to invent selection criteria like “diversity,” which present as inclusive while selecting relentlessly for certain groups over others. The disfavored classes have changed—it used to be Jews, now it’s Asians and whites (and sadly, the way things are going, maybe Jews again soon). But the underlying logic is the same.

It’s a transparent farce, and guys like Zach are probably better off without getting caught up in it. But that’s not the same thing as saying they’d be better off without a liberal arts education, which is still a thing and does still humanize its practitioners. The real shame here is that the question of Zach’s essay remains unanswered: what can college offer that YouTube can’t? The answer is in Plato and Aristotle, whom they used to teach at Harvard. A true education shapes the soul to love what is genuinely good.

You do this face-to-face, in small groups, with someone who cares about you and knows how to give you the right book at the right time. Those of us who are in this business know that even among tech bros it makes the difference between the empty careerist and the virtuous citizen, just as it once set the sharks and players apart from the great statesmen and sages of Athens.

The fact that our elite institutions have largely abandoned their charge of soulcraft is to their deep discredit and accounts, more than any political or financial trend line, for their plummeting worth. But wherever two or three gather to offer real learning—and there are more and more such places these days—the genuinely best and truly brightest can learn what character really means.

Almost three years ago a friend asked me to help him get a classical liberal arts education. I give him weekly reading assignments and he calls me every Sunday for a three-hour discussion. We started with Homer, Herodotus, Thucydides, all the extant Greek Tragedies, Plato’s Republic, Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, The Aeneid, St. Augustine, and now we are one-third the way through Dante’s Divine Comedy. He asked for “every word of every page” and he’s still with me, though I was afraid I was going to lose him at Aristotle. We even took a detour to tackle Joyce’s Ulysses after reading Homer’s The Odyssey, and enjoyed it thoroughly.

It has been the most rewarding thing I have ever done. Exhausting, but rewarding. I’m a retired graphic layout artist, never a teacher. My heart swells when I see the progress he has made.

I appreciate what you said, Spencer, that “You do this face-to-face, in small groups, with someone who cares about you and knows how to give you the right book at the right time.” The chronology of our reading has been in the forefront of my agenda.

I'm thankful for my three "humanizing" liberal arts education experiences, one undergrad and two graduate. In each case the institution and the students knew what the telos was and embraced the path to get there.