Most trivia sites will tell you that the idea for Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark came from Philip Kaufman’s dentist. Kaufman was George Lucas’s buddy, a writer-director who helped Lucas brainstorm ideas for a tribute to the old pulp adventure stories they both loved. In fact, so far as I can tell from this transcript of the story conference, it was actually Kaufman’s blood doctor who told him about the Ark of the Covenant. Kaufman got mononucleosis in college, and his specialist had a weird obsession (everybody needs at least one) with the Ark. “He felt it provided a means of communication with some other extra-terrestrial or God-like or whatever,” Kaufman recalled.

That’s how Indiana Jones ended up chasing the MacGuffin of all MacGuffins from the Holy of Holies, the gold-plated chest that once served as God’s platform and contained the tablets on which he inscribed his laws. Like most sacred objects in the Old Testament, the Ark is described in elaborate detail. Its dimensions and component materials are specified down to the last cubit. The Letter to the Hebrews claims it also contained a jar of manna from the Jews’ time in the wilderness, and the priestly staff of Aaron “which budded” with almonds and blossoms as a sign of God’s favor.

Most importantly, on top of the ark in between two golden statues of the fearsome cherubim, God himself would condescend to fix his very presence and speak. It gave the impression of a throne or a footstool, and after the Jews carried it into the Holy Land it was stored deep within the temple of Jerusalem. It was incredibly dangerous. Reach out to touch it and you might be immolated on the spot; march with it around a city and the walls—given appropriate fanfare—would crumble. Steal it from the temple, as rival nations were wont to do with their enemies’ gods, and you would find your own gods prostrate and broken before the Lord.

It’s a great metaphor for the atom bomb—a devastating weapon that makes its possessors unbeatable—and so naturally both Indy and the Nazis are racing to find it in Raiders. Like the bomb, the Ark is a piece of hardware with such enormous potential that it starts to acquire an aura of fearsome divine mystery. “Jones, do you realize what the Ark is?” asks Dr. René Belloq in the exposition scene. “It's a transmitter! It's a radio for speaking to God.”

As the historian Tom Holland points out on his wonderful podcast, The Rest Is History, an interesting thing about the movie is that for the plot to work, you have to believe the powers of the Ark are real. The conceit is that if Indiana Jones (or the Nazis) can locate this particular object, it truly will serve as a conduit to the source of all knowledge and might. The ark might be a metaphor for us, but in the world of the movie its significance can’t be even remotely metaphorical: it has to be absolutely literal.

Lots of people still believe that it is. As Indiana Jones explains in the movie, the search for the Ark has been going on—in real life—for hundreds and hundreds of years. “They put the Ark in a place called the Temple of Solomon,” says Indy, “where it stayed for many years, ’till all of a sudden...whoosh, it was gone.” No one quite knows when the whoosh happened. It’s certain that the Ark was gone by 63 B.C., when Pompey the Great conquered Jerusalem and entered the inner sanctuary of the second Temple. He found there a few other ritual objects “and a great quantity of spices”—but no Ark. It may have been gone long before, when the first temple was sacked by the Babylonians in the 6th century B.C.

Some say the Ark had been taken long before that, shortly after the Queen of Sheba—or Saba, often understood to be Ethiopia—visited Solomon to admire his riches and his wisdom. This is the story behind the modern-day belief that the Ark is currently in the possession of Ethiopia’s Christians, waiting for its return to the Holy Land at the end of days. Plenty of Jews also believe the Ark will be restored “in the Messianic time,” although they tend to think it was buried in a rock or hidden somewhere by one of the Judean kings just before the Babylonian conquest.

All these prophecies reflect what you might call Indiana Jones theology, in which the object itself—the particular chunks of acacia wood and slabs of gold—contain the power of God within them to this day. Phil Kaufman’s blood doctor’s great grandson wrote a blog post in which he points out that his grandfather—so, Kaufman’s doctor’s son—inherited the fixation with the Ark and wrote a book about it, Talking with God. Its thesis is that the Ark was—or perhaps is—literally radioactive, a piece of ancient communications technology whose physical structure endowed it with special properties.

Of course, there’s another way of looking at all this. Some people take the Ark not so much as an object but as a key word in a symbolic language, meant to embody but not to contain divine truth. One ancient Christian view is that Mary, by carrying Christ in her womb, lived out the ultimate reality that the Ark was meant to signify—“For the holy Virgin is in truth an Ark, gilded within and without,” preached Gregory Thaumaturgus in the 3rd century. If that’s true then there’s nothing all that special about the actual Ark, as in the famous lost box itself. Its gold and wood, even if we could find them, would be a little bit like the buried remains of a friend we dearly loved: we might cherish and preserve them, but we wouldn’t expect to have a conversation with them. Whatever the friend is, in essence, has moved on from these material objects. Wherever he is, “he is not here.”

It will probably be obvious to some readers that this difference in interpretation cuts right through the heart of Church history and Western thought. It is the crux of the dispute over transubstantiation and the real presence of the Eucharist, over icons and iconoclasm. It is even reflected in more secular philosophical disputes like the debate between materialism and its alternatives. You can ask all the same questions about the Ark that you can ask about, say, the human body, or a communion wafer. Is it a hunk of materials, or a vessel for something more? If it’s a vessel, what happens when it falls apart? Does the “something more” go somewhere else?

Go Ask Adam

This is one surprising reason why, for much of history and still today, people have longed to know what language Adam spoke in paradise. It’s essentially the same question as the question about the Ark: when the first human, free of sin, named the first animals, what syllables did he pronounce? Would those syllables, if we could recover them today, have some special connection to the reality of things? Or would they just be arbitrary sounds that were once attached by convention to meanings that now reside in totally different words? If we could speak the original names of the birds and the fish, like some fantasy sorcerer casting runic spells, would we gain power over time and space? What would it take to reconstruct those magic words?

These sorts of questions aren’t idle speculation. They are in some sense the very deepest foundations of modern linguistics. Dante Alighieri, in an unfinished book called De Vulgari Eloquentia, embarked on a process of categorizing languages by their etymological relations which is still going on in the study of prehistoric languages like Proto-Indo-European, Proto-Afro-Asiatic, and so forth. “I intend to enquire into matters in which I can be supported by no authority,” wrote Dante, and he was right. “The process of change by which one and the same language became many” was a subject whose systematic study he was inventing in real time.

Dante started from the argument that language is uniquely human: angels don’t need it, because their spiritual intellects are purely transparent to one another and they always understand each other perfectly. Animals don’t need it, because they would have nothing to say. But since humans have an inner sense of reason enmeshed within a physical body, they need some way of getting their thoughts across perceptibly. “So it was necessary that the human race, in order for its members to communicate their conceptions among themselves, should have some signal based on reason and perception.”

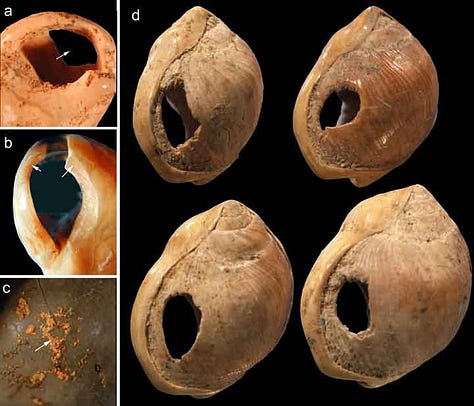

So far as we can tell today, this method of translating thought into speech has been invented only once in the history of our planet. Evolutionary biologists and archaeologists don’t have much to go on in pinning down the date of the first language, but it seems most likely to have been spoken by the time humans left Africa about 60,000 years ago. There are what look like the remains of beads and drawings in South Africa’s Blombos cave, from 80,000 years ago or so, which some take as the earliest known evidence of symbolic thought—a prerequisite for the kind of speech we’re capable of.

In any case, no human groups have ever been discovered that lack the neurological capacity for language, which you might expect if it started evolving after we started spreading around the globe. If that were the case, language would have evolved among some groups in some places, and not in others. But that never seems to have happened.

Another thing that has never happened is that no animal has ever even started to progress toward human speech. There are many famous examples of birds and monkeys learning to string patterns of sound together and associate certain word sequences with certain actions or objects. In 2013, however, linguistics professor Charles Yang reviewed one of the most promising cases, that of the chimpanzee Nim Chimpsky, and showed conclusively that Nim was not capable of understanding true language, in the sense of a rule-based grammar using abstract concepts that can be deployed correctly in a variety of situations. The best he could do was identify phrases like “this apple” with a particular object—he couldn’t move from that to “this cat” or to “this” as applied to other items.

In their difficult but marvelous book Why Only Us, linguists Robert Berwick and Noam Chomsky review the evidence for human uniqueness when it comes to language use. Berwick and Chomsky distinguish between the ability to memorize, control, and produce vocal sounds in sequence—which seems connected to a very old set of brain pathways that we share with other animals like songbirds—and the ability to make the hierarchical connections in the mind that we express with true language. That’s the ability which only humans have ever evolved.

Berwick and Chomsky theorize that the vocal ability we share with birds was then pressed into service as a means of expressing the new kind of thought we had become capable of—a little like the printer attached to a computer. Right again, Dante: we have an inward capacity for reason, and we use our animal bodies to express it in a physically perceptible way. This really is a binary difference between us and the animals, not a gradual continuum on which we exist alongside them.

As a matter of fact, it starts to look as if the Bible and Dante both got a few things right:

All humans and only humans use language.

They started by speaking a single language at one place in the world.

Then that one language spread around and diversified into multiple languages over time.

Dante identifies the origin point of our many languages as—what else?—The Tower of Babel. But he also gives a beautiful interpretation of why the builders in that story stopped understanding each other: they were each working on different parts of the project, so they gradually developed their own words for their specialties and forgot how to talk to other crews. “As many as were the types of work involved in the enterprise, so many were the languages by which the human race was fragmented.”

This is, roughly speaking, how languages really do change over time. As Dante also observes, changing conditions, activities, and locations call forth different patterns of speech among different groups, dividing up languages by space and time until even a citizen of Padua from several generations ago, were he resurrected, couldn’t understand a citizen of Padua today.

He was right about that too. John McWhorter, in his limitlessly engaging book The Power of Babel, describes how the Australian Ngan’gi language transformed within a couple generations, between 1930 and the turn of the millennium. Before writing systems and other technologies come along to fix certain conventions in place, languages still scramble and mutate just as quickly as they did at Babel.

The only exception, Dante thought at first, was Hebrew. The ancestors of the chosen people disapproved of the whole Babel enterprise, which is why they kept apart from it and never got wrapped up in the shop talk that led the other languages to split apart from one another. As such, Hebrew retained its connection to the very first human speech, and maybe even its mystical rightness from before the fall. While other tongues and dialects branched hopelessly outward from Babel in an endless tangle of confusion, Hebrew shot straight and true through time, carrying divine truth. A little like the Ark of the Covenant (if you’re Indiana Jones), the sounds and structure of the Hebrew language were a permanent casing for the Word of God.

And this, Dante seems to have gotten wrong. Whatever language it was that first rang out in Africa, it is even further out of reach than the Ark. It was not exempt from the changes that afflicted Ngan’gi. The Hebrew of the Bible, beautiful and sacred though it is, clearly descends along with many other languages from an ancestor that was long lost by the days of Moses. McWhorter explains at the end of his book why efforts to recover even traces of that ancestor are probably fruitless.

But then, what would it mean if we could recover this Edenic speech?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Rejoice Evermore to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.