Writing is Thinking

Let it come from you; then it will be new.

David Simon, the ex-police reporter who created HBO’s The Wire, was on NPR during the Hollywood writers’ strike a few years ago. The interviewer, Ari Shapiro, asked him whether he might have liked some help from an AI model when he was drafting scenes back in the early 2000s. “If you’re trying to transition from scene five to scene six, and you’re stuck with that transition, you could imagine plugging that portion of the script into an AI and say, give me 10 ideas for how to transition this.”

Simon responded, “I’d rather put a gun in my mouth.”

Me too. I see this a lot now, the idea that chatbots can serve as a conduit between your brilliant ideas and the words needed to get them across. And I hate to be the one to break this news, but that is just not how writing works. You do not have brilliant ideas, sparkling like hidden gemstones in the unseen caverns of your mind, waiting for some helpful android to chisel them into words. What you have are lumpy blobs of disjointed half-thought, flopping and melting into each other like the gunk in a lava lamp.

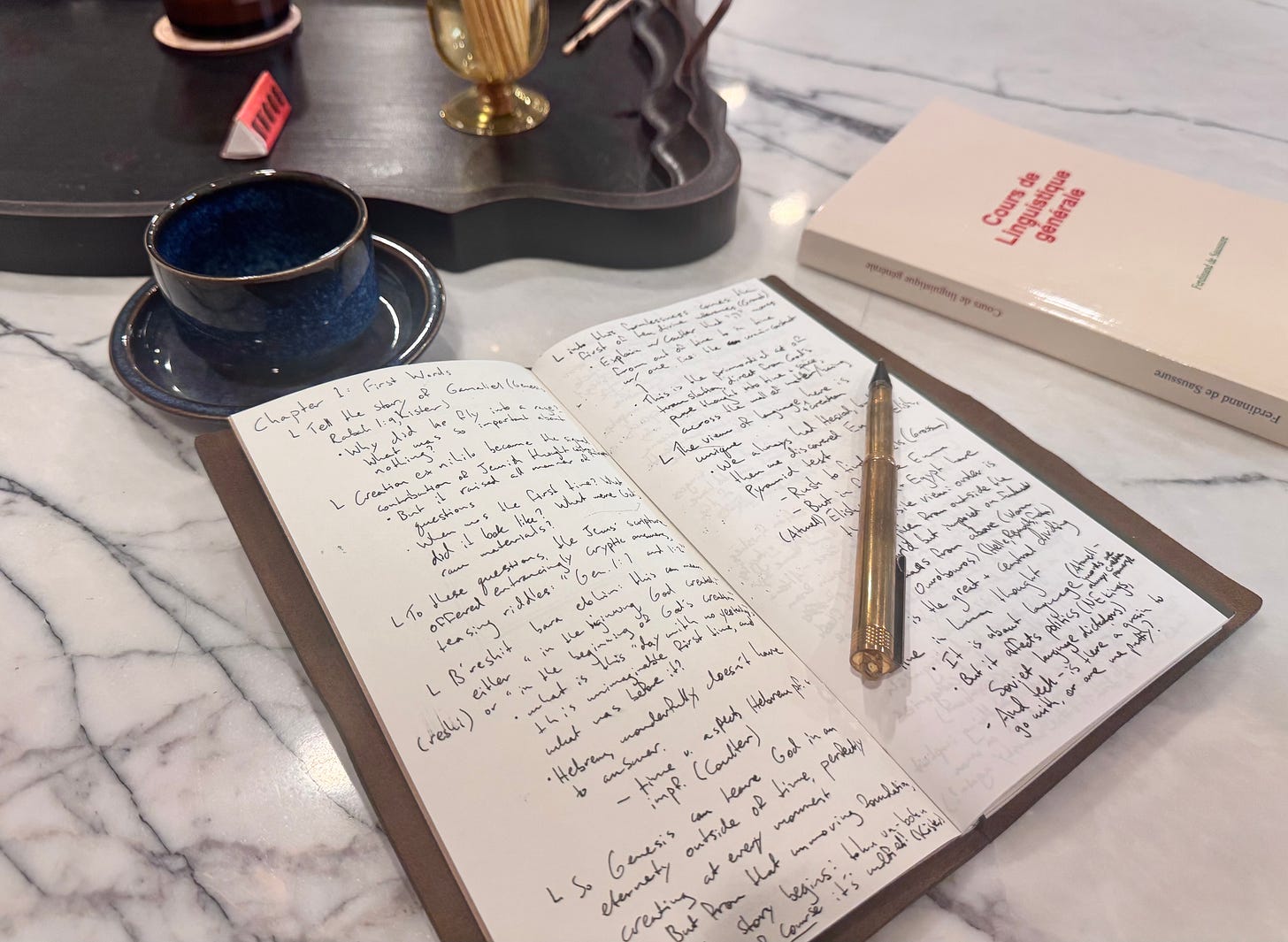

It’s a nasty shock, I know. But if you take the time to sit down and spell those half-thoughts out, you will find their structure is not yet anywhere near as firm and logical as it feels to you. You have to whittle and mold and link each idea until the murky outlines of what you are thinking emerge into a clean and exacting picture, like a sculptor hacking away at his block of marble until he’s gotten rid of everything that doesn’t look like what he sees in his mind. And that is how writing works.

“Writing is thinking. To write well is to think clearly. That’s why it’s so hard,” said the historian David McCullough. It doesn’t actually matter if the product wins a Pulitzer Prize, as McCullough’s nonfiction did. Even a halting anniversary card is worthwhile because, and only because, its words have been dragged painfully into the light from the gloom of semi-consciousness by the person who put them on the page.

If you let an algorithm shape your ideas to fit whatever phrases it selects, from its chewed-up pile of the most commonplace sentiments on the internet, you’re not just letting the machine tell you what to say. You’re letting it tell you how to think. This is one of those things you outsource at your peril. Even if it’s rough around the edges, do it yourself.

There’s good scientific reason to agree with McCullough that language is thought. The evolution of speech, when it occurred in the earliest days of our species, wasn’t a change in the shape of our vocal tracts or the dexterity of our tongues. Our ability to make articulate sounds is old and bestial; we share it with songbirds. What changed to set humans apart was something in the brain: we learned to reason in a new way. “The initial evolution of language,” wrote the evolutionary neuroscientist Harry Jerison, was a shift in the mind that enabled “the construction of a real world.”

When people say they have no inner monologue, what they mean is that their thoughts don’t usually occur to them in the form of sounds and sentences. But the thoughts they do have—in pictures, or impulses, or even melodies—are already a kind of proto-language, an embodiment of ideas in visions or gestures. Like everyone else, they have to sharpen the focus on these rudimentary inklings until they come out precise and clear. For the most part, the best way to do that is with words.

I heard a story the other day: a man’s wife of more than 60 years was dying. He didn’t know how to tell her he loved her in words, so his daughter showed him how to ask ChatGPT. “It produced a poem. A long poem. He said it perfectly captured his feelings about his wife.” I hope it brought them both some comfort—truly, I do. But all I can think about is how many generations of social failure it took to reach the point where that old man was sitting by that bedside, with only a machine to tell him how to grieve.

I know it’s painful and embarrassing. Believe me, I confront it every day. But rummaging around within your soul and drawing out the stirrings that you find there into words, planing down the words until they’re trim and fit to purpose—none of this can be automated without cost. The privilege and the burden of your inner life are yours. There’s nothing you could gain that would be worth giving them away.

Watch the latest from Young Heretics:

Some people say they have no inner monologue. How is that possible? I have a constant inner monologue. So, no thoughts in their heads, they just live with emotions. That actually explains a lot.

Thank God you said this Spencer! I knew this for myself, but did not realize it was true for everyone. I practice "lectio divina"--a form of prayer in which one takes a phrase from scripture (or other writing), and ponders it so as to find the meaning in it for oneself. In my way of doing it, I write down my ponderings. I started doing it that way so as to keep distractions to a minimum; writing was a way to keep focused. But I have found that as I write, thoughts come from my pencil that I didn't know were there. In this way, my thinking about scripture has over the years become much more clear and real. I'm not in the way of becoming St. John Henry Newman, or any other great thinker, but my own thinking has clarified and broadened.