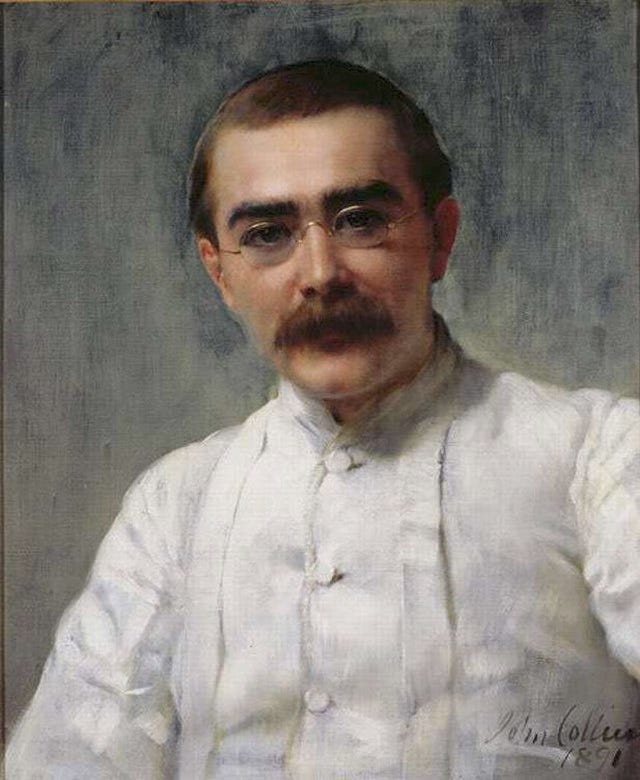

People always think they’re smarter than Rudyard Kipling’s “If—.” In literary circles it’s a rule that admiration of the poem must be qualified, usually with disclaimers to show you are aware of the author’s moral and literary defects. T.S. Eliot condensed this attitude perfectly in one phrase when he called Kipling “a good bad poet”—the kind whose poetry you can’t help enjoying, but not for lack of trying. Sophisticated people are embarrassed to like it.

They are even more embarrassed that so many other, unsophisticated people like it, and in such unsophisticated ways. Kipling himself was a little dismissive about seeing his verses of fatherly advice “printed as cards to hang up in offices and bedrooms; illuminated text-wise and anthologised to weariness.” Those of us who flatter ourselves on our critical taste in poems don’t like to find ourselves in league with the kinds of people who frame them in powder rooms.

The crowning insult is the poem’s enduring popularity, the fact that the wrong people—of whom there are so many—adore it. This always has to be explained as if it were some mystifying puzzle. But the only mystery is how the good and the great can be brought so low as to wallow happily in the kind of verse that can be painted in cursive on a wood block.

We anointed would prefer if we could at least enjoy Kipling in a different, special way, which is why we make our disclaimers. They are there to enforce the kind of critical distance usually referred to now as “ironic,” like struts wedged between us and the poem to protect us from being normal.

George Orwell understood this. “The fact that such a thing as good bad poetry can exist,” he wrote, “is a sign of the emotional overlap between the intellectual and the ordinary man.” Most intellectuals don’t like the thought of too much overlap and do everything they can to minimize it. Even Orwell must have sneered just a little when he called poetry like Kipling’s “a graceful monument to the obvious.”

Invectives like “obvious” allow us to take our revenge on the poem for moving us so deeply. There are others: “a classic of righteous certitude” written by “an icon of obnoxious wrongness.” “pedestrian and sanctimonious poetry.” “Jingoistic nonsense.” It’s difficult to resist the conclusion that what annoys critics about “If—” is what annoys teenagers about their fathers: it’s too stern, too rigidly conventional, and above all too confident in being right.

Teenagers roll their eyes at their fathers’ advice when they think they already understand the basics. Critics roll their eyes at Kipling when they think they already understand his perspective. He sounds to them like someone riding high on the surge of Britain’s empire, flush with success and unwilling to betray the slightest waver of self-doubt or admit to any kind of defeat.

But this is to misunderstand the poem as drastically as we all once misunderstood our fathers. In reality, “If—” is saturated with failure. Disaster is its atmosphere, from the very first couplet: “If you can keep your head when all about you / Are losing theirs and blaming it on you.”

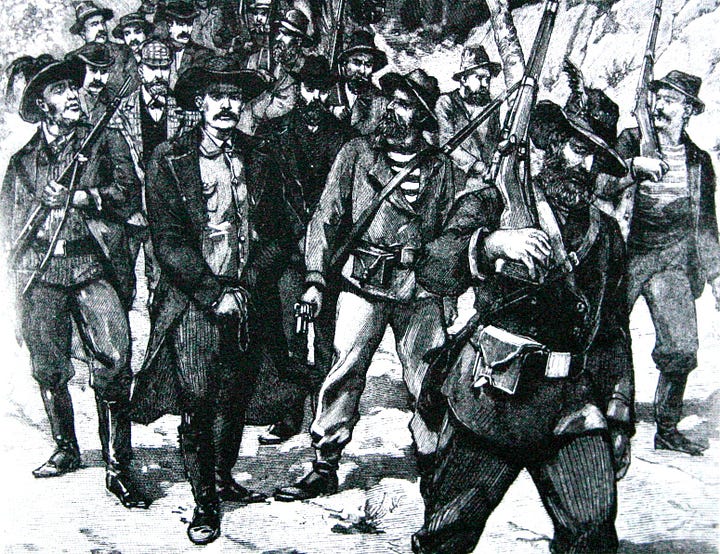

Kipling’s inspiration was Leander Starr Jameson, an eminent Victorian known chiefly for leading a failed raid on Boer territory in South Africa. Jameson was left exposed and humiliated after catfighting authorities threw the mission into confusion; he ended up serving 15 months in prison thanks to their indecision. The secret and the genius of “If—” is that it’s not jingoistic or triumphalist at all. It assumes a world of painful injustice and shame for good men.

The true man of the poem is doubted by everyone, “lied about,” “hated.” Under those conditions Kipling’s homespun wisdom no longer feels quite so “obvious.” It feels more like water that someone offers you at the foot of a tall mountain: easy to reject in the cool ease of base camp, bitterly lamented for its absence after hours on the scorching trail.

That’s why the poem ages so well: it only comes into its own when you find yourself in need of it. The plodding meter of the verses, easy to deride, is what keeps them drumming through your head when pain and exhaustion otherwise make thinking impossible. Even the rhythm is like fatherly advice, patiently repeating itself over the objections of scornful children who will privately thank God for it in their hours of weakness and desperation.

Orwell wrote that for Kipling, “history had not gone according to plan”: as the empire tottered and its spirit passed from the earth, his poetry fell sharply out of favor among those in the know. But it would be a mistake to imagine that Kipling’s philosophy depended for vindication on worldly victory or elite approval. “If—” never promises success to those who follow its instructions. It promises manhood, which can “meet with Triumph and Disaster / And treat those two impostors just the same.”

Rejoice evermore,

Spencer

Listen to the latest from Young Heretics:

I think we all know instinctively that as fallen creatures we can never live up to what this poem asks of us, at least not nearly as often as we would like to. Yet we also instinctively know that it’s what we should constantly strive for. I believe that’s why it appeals so much to the common man and chafes the elites.

As a member of the unwashed masses that likes IF, highly recommend this version: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7G_Bun6Aecg